.gif)

|

A human time bomb is ticking and the day could arrive when antibiotics are no longer effective against biological infection. “If that happens, it will turn the clock back to the dark ages before penicillin,” he added. The researchers are led by Principal Investigator Prof Kwok-yin Wong, head of PolyU’s Department of Applied Biology and Chemical Technology. Their biosensor fluoresces when it detects even a trace amount of antibiotics. World attention was drawn to the biosensor when it was reported in an international professional magazine and later when it won a gold award in the 2004 China International Invention Exposition held in Shanghai. Patents are currently pending in the US, Europe and China.

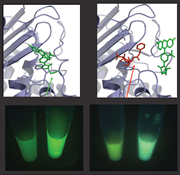

Beta-lactamase enzymes are secreted by bacteria when any beta-lactum antibiotic is sent to kill them. In this way, bacterial resistance to antibiotics soon builds up. “Nature is very clever. It generates different weapons to fight different drugs,” said Dr Leung. To build the antibiotic-detecting sensor, the researchers used the same beta-lactamase enzymes and, as Dr Leung puts it, “turned the bad guy into a good guy doing something useful.” With chemical modification, they found the enzymes fluoresced in the presence of antibiotics. This was done by attaching an environment-sensitive, fluorescent molecule to a flexible loop of the enzyme. Under normal circumstances when the enzyme is not in contact with antibiotics, the molecule does not fluoresce due to its position in the enzyme. But in the presence of antibiotics, the molecule moves its position as the enzyme attempts to bind with the antibiotic and destroy it. With this changing environment, the molecule emits a strong light. “We are the first to use these enzymes to make a biosensor,” said Prof Wong. “Previously people didn’t believe enzymes could be used as biosensors because they catalysed and performed their enzymatic activity very quickly. “What we did was to modify amino acids on the enzyme in such a way that we changed the enzyme from a catalytic enzyme to a binding protein. “In this way we slowed down the enzymatic activity by more than 2,000 times.” Instead of fluorescing for about 30 seconds, as the antibiotic is not rapidly destroyed by the enzyme it fluoresces for a few hours, he added. Principal Investigator Prof Kwok-yin Wong : bckywong@polyu.edu.hk |

||||||||||||||||||||||||